Now Reading: Manhattan Bridge

-

01

Manhattan Bridge

Manhattan Bridge

Hey everyone, welcome back to *Brooklyn Echoes*, the podcast that keeps the borough’s legends and memories alive. I’m your host, Robert Henriksen.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to this captivating narration on the Manhattan Bridge, a masterful feat of engineering that gracefully arcs over the East River, linking the vibrant neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn. Often overshadowed by its more famous neighbor, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge stands as a testament to early 20th-century innovation, urban expansion, and the relentless drive of New York City. Opened in 1909, this suspension bridge has carried millions of vehicles, trains, pedestrians, and cyclists, evolving from a controversial project to an indispensable artery of the metropolis. As we delve into this story—covering its origins, arduous construction, design breakthroughs, trials, and enduring legacy—picture yourself strolling its pedestrian path, with the hum of subways below and the skyline unfolding before you.

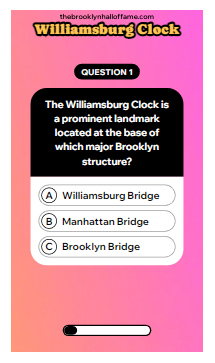

Our tale begins in the late 19th century, amid New York City’s explosive growth. With the Brooklyn Bridge already straining under traffic since 1883 and the Williamsburg Bridge under construction, city planners eyed a third East River crossing. In 1898, the project was authorized as “Bridge No. 3,” but by 1902, it earned its name: the Manhattan Bridge. The New York City Department of Bridges, under Commissioner Gustav Lindenthal, spearheaded the effort. Lindenthal, a renowned engineer, initially favored eyebar chains for suspension but clashed with experts who advocated wire cables—a debate that delayed the project by two years and inflated costs by $2 million. Ultimately, wire cables won out. Construction officially commenced on October 1, 1901, with a total estimated cost of around $26 million (equivalent to over $900 million today), though it ballooned to $31 million due to overruns.

The design was revolutionary, helmed by Leon Moisseiff, a young engineer who would later contribute to icons like the George Washington Bridge but is infamously linked to the ill-fated Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Moisseiff applied Josef Melan’s deflection theory for the first time on a major span, positing that the bridge’s own weight and flexibility could distribute loads without massive stiffening trusses, making it lighter and more economical than predecessors. The result: a sleek suspension bridge with a main span of 1,470 feet—the third-longest in the world at the time—a total length of 6,855 feet including approaches, and a width of 120 feet. Towers soared 336 feet high, built from steel and clad in stone, while the four main cables, each 21 inches in diameter, comprised 37 strands of 278 wires each, totaling over 16 miles of wire per cable and weighing 8,500 tons. The bridge featured a double-deck configuration: an upper level for roadways and pedestrians, and a lower for trains and additional lanes. Architectural flair came from Carrère and Hastings, who designed the Beaux-Arts-style triumphal arch and colonnade at the Manhattan entrance, complete with granite pylons, sculptures, and ornate details evoking Parisian grandeur.

Construction was a grueling saga, overseen by chief engineer Othniel Foster Nichols after Lindenthal’s resignation in 1903 amid political scandals. Work began with pneumatic caissons—watertight chambers sunk into the riverbed for foundations. The Brooklyn caisson was installed in 1902, the Manhattan in 1903, but tragedy struck: three workers perished from decompression sickness, or “caisson disease,” on the Brooklyn side alone. Foundations were finished by 1904, anchorages—massive concrete blocks securing the cables—by 1907, and the towers by 1908. Steel fabrication by the Phoenix Bridge Company involved Warren trusses for the approaches, a first for suspension bridges. Cable spinning commenced in 1908, with workers traversing a temporary footbridge to lay the wires. Challenges abounded: harsh weather, material shortages, legal battles over contracts, and the displacement of hundreds of families through eminent domain, particularly in Chinatown and the Lower East Side. A 1910 fire, just months after opening, damaged cables and steelwork, requiring $50,000 in repairs.

Despite these hurdles, the bridge opened to great fanfare on December 31, 1909, with Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. leading the ceremony. Initially, only the upper roadway and pedestrian paths were ready; streetcar tracks followed in 1912 (operating until 1929), and subway service—via four tracks for the B, D, N, and Q lines—began in 1915. Early tolls of 5 cents for vehicles and 1 cent for pedestrians were abolished by 1911. The bridge quickly proved its worth, slashing ferry reliance and boosting real estate in Brooklyn, transforming areas like Dumbo from industrial warehouses to trendy lofts and spurring Jewish migration from Manhattan’s crowded tenements.

But triumph turned to trouble. The uneven placement of subway tracks on the outer edges caused the bridge to twist and tilt under train loads—a flaw Moisseiff hadn’t fully anticipated. By the mid-20th century, cracks appeared in beams and eye-bars, leading to restrictions: trucks banned in 1956, buses limited in 1978. A 1953 inspection revealed severe corrosion, halting subway service intermittently. Major crises peaked in the 1980s; by 1982, the structure was deemed unsafe, prompting an $800 million reconstruction from 1982 to 2004. This involved replacing beams, stiffening the deck, realigning tracks to the center for balance, and seismic upgrades. Federal funding covered much, but disruptions were immense: subway shutdowns, lane closures, and traffic chaos. Further woes included a 1986 partial collapse scare and 1988 emergency repairs. In 2010, an $834 million project replaced the suspender cables and added necklace lighting, wrapping up by 2013. More recently, a 2018-2021 contract worth $75.9 million rehabilitated trusses, drains, railings, and historic ornaments, ensuring longevity.

Today, the Manhattan Bridge thrives as a multifaceted lifeline, carrying seven vehicular lanes (four upper, three lower), four subway tracks serving over 300,000 riders daily, a south-side pedestrian walkway, and a north-side bikeway. As of 2024, it sees about 70,000 vehicles, 3,400 pedestrians, and 6,400 cyclists each day. Managed by the NYC Department of Transportation, it’s part of I-278 and subject to congestion pricing since 2023, with variable tolls for Manhattan-bound traffic to ease gridlock. Designated a New York City Landmark in 1975, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983, and named a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 2009—its centennial year—the bridge symbolizes resilience. Its Beaux-Arts arch, restored in 2001 for $11 million, houses public spaces like a plaza, while sculptures by artists like Daniel Chester French add artistic depth.

Culturally, the Manhattan Bridge is woven into the city’s fabric. It inspired Edward Hopper’s 1928 painting “Manhattan Bridge Loop,” capturing its industrial poetry. Under its Manhattan ramps, a bustling Chinatown mall and theater thrive, while Brooklyn’s side birthed the Dumbo arts scene. It’s featured in films, literature, and idioms, representing the bridge between immigrant pasts and modern futures. Yet, vulnerabilities persist: post-2024 Baltimore bridge collapse, assessments confirmed its robustness, but ongoing maintenance battles corrosion from the salty East River.

As we conclude, the Manhattan Bridge endures as more than steel and stone—it’s a narrative of ambition, error, and redemption. From Moisseiff’s bold theory to the workers’ sacrifices, it links not just boroughs but eras, reminding us that true progress spans challenges. Next time you cross, pause to appreciate this unsung hero, quietly powering the pulse of New York.

If you like this podcast, Check out our new Brooklyn Echo’s Audio podcast at The Brooklyn Hall of Fame were we have been recording episodes to stream at your favorite streaming services like Apple or Spotify.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01A Journey Through the Life of Gene Tierney

01A Journey Through the Life of Gene Tierney -

02The Inspiring Journey of William DeMeo

02The Inspiring Journey of William DeMeo -

03A Journey Through the Life of Bea Arthur: Comedian & Actress

03A Journey Through the Life of Bea Arthur: Comedian & Actress -

04A Deep Dive into Debra Messing’s Life and Career

04A Deep Dive into Debra Messing’s Life and Career -

05Exploring the Life of Edith “Didi” Conn: A Journey through History

05Exploring the Life of Edith “Didi” Conn: A Journey through History -

06A Comprehensive Look at Edie Falco’s Inspiring Journey

06A Comprehensive Look at Edie Falco’s Inspiring Journey -

07Jimmy Smits: A Look at His Life and Career

07Jimmy Smits: A Look at His Life and Career