Now Reading: Williamsburg Brooklyn

-

01

Williamsburg Brooklyn

Williamsburg Brooklyn

Hey everyone, welcome back to *Brooklyn Echoes*, the podcast that keeps the borough’s legends and memories alive. I’m your host, Robert Henriksen.

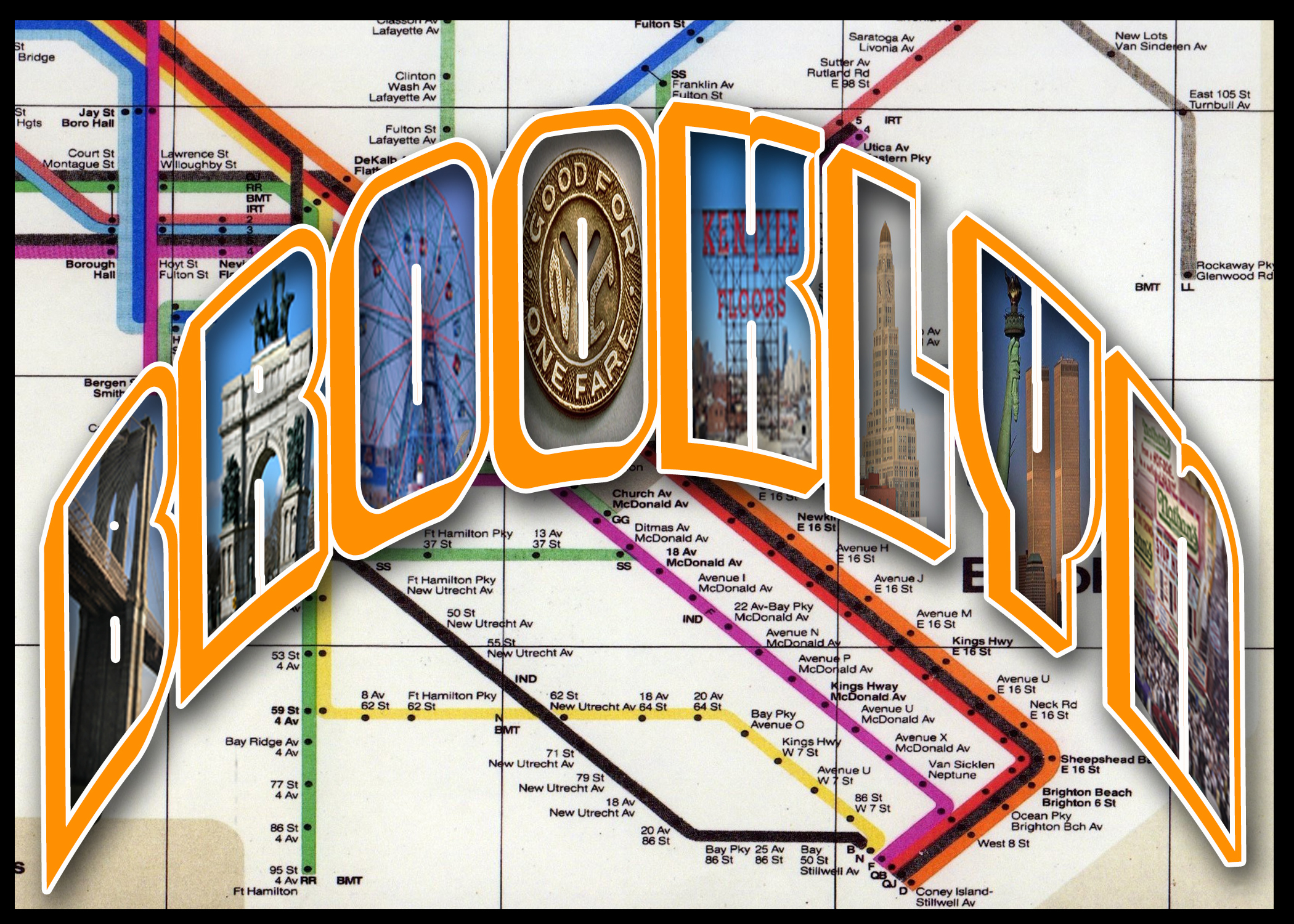

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to this engaging narration on the Williamsburg Bridge, a pioneering engineering achievement that spans the East River, binding the eclectic Lower East Side of Manhattan to the vibrant Williamsburg neighborhood in Brooklyn. Opened in 1903, this suspension bridge not only revolutionized urban connectivity but also marked a bold step in bridge design, becoming the longest of its kind at the time. As we unfold this story—encompassing its inception, grueling construction, innovations, setbacks, and lasting influence—envision yourself on its pedestrian path, with the wind carrying echoes of immigrant tales and the cityscape alive around you.

The Williamsburg Bridge’s origins trace back to the late 19th century, a era of rapid urbanization in New York. With Brooklyn’s population surging—reaching over a million by 1890—and the Brooklyn Bridge already overburdened since 1883, the need for another East River crossing became critical. In 1895, the New York State Legislature approved the project, initially dubbed “East River Bridge No. 2.” Leffert Lefferts Buck, a seasoned civil engineer known for his work on Niagara Falls bridges, was appointed chief engineer in 1896. Buck’s vision was ambitious: a suspension bridge with a record-breaking main span of 1,600 feet, surpassing the Brooklyn Bridge by five feet, a total length of 7,308 feet including approaches, and a width of 118 feet to accommodate roadways, trolley tracks, elevated rail lines, and pedestrian walkways. The design incorporated steel towers rising 335 feet high—the first major bridge to use all-steel towers instead of stone masonry, reducing weight and cost while enhancing strength. This shift to steel was revolutionary, allowing for taller, lighter structures and setting a precedent for future bridges like the George Washington.

Construction commenced on October 28, 1896, with an initial budget of $10 million that eventually ballooned to $24.2 million due to delays and material costs. The process began with sinking pneumatic caissons for the foundations—enormous airtight chambers where workers excavated the riverbed under compressed air. The Manhattan caisson reached 78 feet deep, the Brooklyn 114 feet, but this innovative method came at a human cost: over 30 workers suffered from caisson disease, or “the bends,” with several fatalities from decompression sickness, explosions, and fires. A notable incident in 1901 saw a caisson fire rage for days, requiring heroic efforts to extinguish. Political corruption under Tammany Hall further complicated matters; Buck faced interference, leading to his replacement in 1902 by Washington A. Roebling as consulting engineer, though Buck returned briefly before his death in 1909. Labor strikes in 1900 halted progress for months, demanding better wages for the largely immigrant workforce, including Irish, Italian, and Eastern European laborers earning as little as $1.75 per day.

The towers, fabricated from nickel steel, were erected by 1900, their lattice design criticized as “ugly” and “utilitarian” compared to the Gothic elegance of the Brooklyn Bridge. Cable spinning started in 1901, weaving four massive cables—each 18.75 inches in diameter—from 7,696 galvanized steel wires per strand, totaling 17,500 miles of wire. A temporary footbridge aided workers, but accidents were rife: falls, snapped wires, and a 1902 collapse of a traveler platform killed two. The stiffening truss deck, 20 feet deep, was innovative for its time, incorporating deflection theory elements that influenced later designs. Approaches included massive anchorages weighing 200,000 tons each, and ornate terminals blending functionality with modest Art Nouveau details.

After seven years of toil, the Williamsburg Bridge opened on December 19, 1903, to jubilant crowds. Mayor Seth Low and 20,000 spectators attended, with fireworks and parades marking the event. It was the first East River bridge to carry elevated trains, debuting service in 1904, alongside trolleys until 1948 and roadways for horse-drawn carriages evolving to automobiles. Tolls started at 1 cent for pedestrians and 5 cents for vehicles but were eliminated by 1911. In its early days, the bridge facilitated massive immigration waves, linking Jewish and Puerto Rican communities in the Lower East Side to emerging enclaves in Williamsburg, boosting commerce and real estate. A 1905 panic from false collapse rumors caused a stampede, injuring dozens and prompting reinforcements.

The 20th century tested the bridge’s resilience. By the 1920s, it lost its longest-span title to the Bear Mountain Bridge in 1924. Traffic surged, leading to a 1930s widening and the addition of reversible lanes. World War II saw it painted camouflage gray for protection. Post-war, neglect set in: corrosion from salt air and heavy loads cracked beams, culminating in a 1988 emergency closure for all traffic after inspectors found severe rust—dubbed a “bridge to nowhere” crisis. A $1 billion reconstruction from 1983 to 2003 replaced the deck, cables, and trusses, incorporating seismic retrofits. Subway tracks, serving the J, M, and Z lines, were realigned for balance, carrying over 200,000 riders daily. In the 2010s, a $300 million project added a protected bike lane in 2019, now one of NYC’s busiest with 7,000 cyclists daily, and LED lighting in 2020 for energy efficiency.

Recent years have highlighted ongoing challenges. As of 2025, NYC’s aging infrastructure woes persist; a May 2025 report noted 118 bridge sections in poor condition citywide, including parts of the Williamsburg rated “fair” but requiring $50 million in urgent repairs for corrosion and fatigue. Managed by the NYC Department of Transportation, it handles 100,000 vehicles daily as part of the BQE (I-278), with congestion pricing implemented in 2023 for southbound traffic. A 2024 incident involved a minor vessel collision, but the bridge’s overbuilt design—six times stronger than needed—averted disaster.

Culturally, the Williamsburg Bridge is an icon of transition and creativity. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 2003—its centennial—and a NYC Landmark in 1983, it inspired artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, who painted its stark lines, and filmmakers capturing its gritty allure in movies like “Once Upon a Time in America.” It’s a symbol in literature, from Henry Miller’s works to modern street art under its ramps in the Dumbo and Williamsburg arts districts. Hidden gems include wine vaults in its anchorages, once used for storage, and its role in protests, like the 2020 Black Lives Matter marches. Post-9/11 security added cameras and barriers, while sustainability efforts include solar panels installed in 2022.

As we wrap up, the Williamsburg Bridge stands as a bridge of reinvention—from industrial workhorse to hipster haven, embodying New York’s dynamic spirit. Its steel framework, forged through sacrifice and ingenuity, continues to connect diverse worlds, reminding us that true links endure beyond stone and wire. Next time you cross, feel the history pulsing beneath your feet.

If you like this podcast, Check out our new Brooklyn Echo’s Audio podcast at The Brooklyn Hall of Fame were we have been recording episodes to stream at your favorite streaming services like Apple or Spotify.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01A Journey Through the Life of Gene Tierney

01A Journey Through the Life of Gene Tierney -

02The Inspiring Journey of William DeMeo

02The Inspiring Journey of William DeMeo -

03A Journey Through the Life of Bea Arthur: Comedian & Actress

03A Journey Through the Life of Bea Arthur: Comedian & Actress -

04A Deep Dive into Debra Messing’s Life and Career

04A Deep Dive into Debra Messing’s Life and Career -

05Exploring the Life of Edith “Didi” Conn: A Journey through History

05Exploring the Life of Edith “Didi” Conn: A Journey through History -

06A Comprehensive Look at Edie Falco’s Inspiring Journey

06A Comprehensive Look at Edie Falco’s Inspiring Journey -

07Jimmy Smits: A Look at His Life and Career

07Jimmy Smits: A Look at His Life and Career